- Home

- Harlan Ellison

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Page 9

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Read online

Page 9

"You're late," Bobby said, dropping his voice into the range he used for inept switchboard operators.

Yaffa waved away the comment, settled down between them and pulled a pop-lid tin of pudding from his djellabah. He produced a folding military-issue spoon, yanked off the lid of the pudding tin, and began eating. I have been snaking and moving, great gentlemen. Taking roads where no roads exist, ducking and dogging—"

"I think you mean 'dodging'," Loder said.

"...ah! Even so. And as a regrettable consequential, I confess to a fractional tardiness." He paused, spooned pudding into the foliage of his beard, then said: "And pray kindly tell me, great gentlemen, which among the multitude many is your favorite American blues guitarist?"

They stared at him. The stars shone like ice, the glyph lay in Bobby's hand brightly lit, the distant slicing of a jackal's cry echoed past them, and they stared.

"For my own good self," Yaffa said, "there was none more exalted than Blind Lemon Jefferson, though I now and yon feel that Son House was the nonpareil of Delta blues. And which of them whom you adore is your favorites, great sirs?"

Two hours later, after Yaffa had relieved himself and slept, they moved out. Toward Mamoula, that their guide called Ma'alula, 33°50'N, 36°33'E, where speaking neither Arabic nor Kurdish would be of any help. For in Mamoula, in the mountains, though they have lost the ability over the centuries to write it, the hidden residents speak the Aramaic of Jesus's time, precisely as the Christ spoke it. Toward Mamoula, carrying the light.

These were the direct descendants of the Hittite Empire that had ruled the Levant till the end of the Late Bronze Age. Craggy men naked beneath their djellabahs, their curved knives hanging by a thong across their chests and below their armpits; wearing the traditional skullcaps; sandals or handmade boots according to their occupation. Dark eyes studying the two infidels and the intruder from some great city in the lowlands—Hamath, or even Damascus, of which they had heard. These were the blood of the Akhlamu, and the Aramaeans; sinew of Canaanites and the Aramaean neo-Hittites who crushed Shalmaneser III at the battle of Qarqar in 853 B.C.E.

They had driven through the night and late into the next day. There had been a Land Rover, fully stocked; even to several bottles of San Pellegrino and Vichy water. Yaffa had babbled happily of Lightnin' Hopkins and Lonnie Johnson, and of having worked briefly with Malkin of the MOSSAD, who had walked up to the fugitive Eichmann on Garibaldi Street in Buenos Aires in I960 and said, "Un momentito, senor." Bobby Shafka had slept fitfully, unable to find a place for his spine; and Dennis sat silently (save when he was forced to make a sound in response to Yaffa's paeans in praise of Tampa Red's left hand). He smoked his pipe and held the glyph, and found himself sinking deeper and deeper into fear. This was more than stone. What had he been thinking of, to let Bobby suck him in this way?

The Rover hit a scree as they began their shallow ascent, and Loder was knocked against the door with enough force to jam his crazybone. He gave a yelp. Bobby slept on. Yaffa chuckled lightly, navigated through the sheet of coarse debris mantling the mountain slope, and spoke softly to his shotgun passenger.

"Will you be taking treasures from the land, Dr. Loder?"

There was none of the punkah-wallah "sahib" burlesque in his voice now. He spoke flawless English, with only the faintest trace of the Levant.

Loder looked at him. Yaffa's face was faintly lit by the dial glow from the dashboard. His features were sharper now; almost nothing left of the simpering pouch-cheeked caricature that had found them near the sphinx gate. "Perhaps," Loder answered. They rode in silence for a while, then Dennis said, "I was wondering when you'd divest yourself of the funnyface."

"A man must play many parts to survive, Doctor.

"And what will you do with these treasures...should they exist?"

"I'll take them back and use them to help decipher the history of the land, and the people who came and went here."

"You know Hafez al-Assad has decreed death on the spot for archaeological pilferage. This does not frighten you?"

"Yes, it frightens me."

"But not as much as you are frightened by that glowing stone seal in your vest pocket, do I perceive correctly?"

Loder placed the little golden pipe mirror atop the bowl and puffed the tobacco to a cheery glow.

"That has a marvelous bouquet," Yaffa said, watching the ruts that served as road, skirting the talus at the foot of a steep declivity. "Oriental tobaccos? Latakia; perique, perhaps?"

Loder shook his head. "One whiff of latakia and I'm on my back. No, it's just some Virginia, and a nice toasted cavendish. Why have you revealed yourself to me, and not to my partner?"

"Because I think you have been duped by friendship. I think that you regret this expedition, that you are a decent sort of man; and I know you are frightened."

"You saw the glyph glowing?"

"Yes. When I found you. I was above you, studying you, for many minutes before I declared myself."

"And you don't much care for Bobby, is that it?"

Yaffa shrugged. "He is like most men. He lives on the edge of the moment. He is like the dust. It lies a while, then is blown away."

"He's my friend. We grew up together. I hope whoever hired you to guide us can count on your fidelity to both of us. We're in your hands, you know."

Yaffa turned his head for a moment. He looked at Loder, and said, "Yes, I know that. And we are all three in the hands of Allah."

"Does Allah have any knowledge of this stone seal? Some random bit of minutiae that might make our little journey safer and more productive?"

The Syrian brought the Land Rover to a slow, smooth stop. He turned in his seat and stared at Loder. "I was paid to come and meet you, to take you to Ma'alula where, I was told, you will put to advantage some information as to the location of a very old Hittite tomb. I was told no more than that, and in truth, I need know nothing more. But now I have seen this strange compass you follow; and I say this to you, Dr. Loder: if it were I, my fear would send me in another direction. Where we go is not merely into the mountains. Where we go is back in time. These people live as they lived four thousand years ago, for the most part. They have been touched by civilization, but it is a gentle, not a lingering touch. What they know, they know in their blood and bones. And if there were not others depending on me for the money I have been paid, I would never have spoken to you back at the broken stones. I would have slipped away and left you to fend for yourselves."

He stared out the windscreen and added, "My greatest fear is that Allah may feel the need to close his hands around us harshly." And in a silent moment he shifted out of neutral, into low, and began climbing once more.

Now it was day, and they moved carefully through the hard-packed clay of Mamoula's only street. Above them the mountains loomed painfully, old men with arthritis.

No one spoke to them. Women carrying early morning water in leather sacks stepped between the wattle and daub buildings to avoid them. But they were watched. They passed three small children playing in a mud puddle. An impossibly old man sitting on a stool in front of a house, holding a crooked staff as if it were a symbol of office, closed his eyes and feigned sleep as they detoured toward him. They retreated to the center of the street. Each time Yaffa approached a man, young or old, to ask a question—the object of his attention turned his back and walked away.

At last, they stood at the foot of the rutted trail that climbed from the end of the village street, through talus slides, into the higher mountain passes. They had gone from one end of Mamoula to the other, and there was no help.

Yaffa said to Loder, "I know how to do this. Will you let me do what is necessary?"

Bobby answered. "Do what you have to do."

Loder said, "It doesn't entail hurting anyone, does it?"

"No," Yaffa said. "I have children of my own."

"Just do it, man," Bobby said urgently. "I didn't come all this way to go back empty. This is it for me!"

Yaffa turned and walked back down the street as the eyes of the town followed. Bobby and Dennis stood where they were, and watched. Yaffa went to the children playing in the mudhole, stooped, and lifted a five-year-old little girl high in the air over his head. The child, taken by surprise, was dumbfounded for a moment, then laughed as the squat, cherubic stranger whirled her around high above. She laughed and laughed, until the mother came running from one of the houses, shrieking in a lost tongue. Yaffa stood his ground as the woman flew at him. He set the child on his shoulder and raised a hand to stop the woman. Here and there on the street others took a step toward the intruder; then they waited. He had the child.

Yaffa spoke quickly and earnestly to the woman. Neither Dennis nor Bobby understood a word. Bobby leaned toward Loder and whispered, "What language?" Dennis shook his head. "Not Arabic, not Kurdish. I don't know. It may be Aramaic, or some dialect that's transitional. I've only heard Aramaic spoken once, at a university lecture. It didn't sound anything like that. I have no idea what he's saying...but I can guess."

He paused. "If the woman brings a man to him, I think I know what's going on."

As if to Loder's surmise, the woman turned toward a group of men halfway down the street. She took several steps toward them, and one of the younger men shouted to her. She stopped, looked back at Yaffa and the child, as if insuring their immobility, and then shouted back something to the young man.

In a moment, after hurried conversation in the group, the young man strode manfully to Yaffa, stood before him, and held out his arms for the little girl. The child, gurgling at her father, was content to perch on Yaffa's shoulder.

Yaffa spoke softly but at length to the young man.

Finally, the man nodded, and indicated Yaffa should follow him. Yaffa gestured to Bobby and Dennis to come; and he turned and walked along behind the young man; toward the ancient on the stool before the rude domicile. The young man went to the withered elder, kneeled before him deferentially, and spoke passionately. The old man listened for a time, then stopped the younger with a raised finger. He looked up, directly at Yaffa, and nodded almost imperceptibly. Yaffa instantly handed the child to the woman dogging his footsteps,

The family rushed away, and Yaffa motioned Shafka and Loder to follow him as the old man slowly and painfully rose and went into the hut. They followed.

The Land Rover was abandoned two days' climb into the Qalamun Sinnir. The two guides assigned by Mamoula's oldest resident had been terrified of the vehicle, and they had ridden ahead on stumpy-legged, hairy ponies, leading three more by tether reins. Above six thousand feet the trail that was no trail vanished entirely, and the slopes covered with garigue—a degenerate Mediterranean scrub—and maquis—a thick scrubby underbrush—became too steep; and the shrub ripped loose and clogged the wheel wells. They left the vehicle and mounted the ponies.

For the most part, they rode in silence. Once, Yaffa fell back and asked Loder, "Now I must know. How do we come to this place, of all places? Is it the writing on the seal?"

Loder mopped his brow. "No, we can't decode the engravings. It was more than a hundred years ago, and it was just like what happened to us in Mamoula. A stone turned up, with carvings. They traced it back to Hamah, but the people wouldn't tell them where they were. Eventually, they were located, and that formed the first body of information we had on the Hittite Kingdom.

"The seal was also found. But it was held by one in the employ of the Subhi Pasha, who delivered it to him with everything he had learned of its origin. Which wasn't much. It was a minor find, and lay unrecognized until 1980 when an art cache in Baghdad was rifled, and the glyph began its travels through the international art theft underground."

Bobby, who had been listening, broke in. "During my brief and really terrific stay at that country club with bars they called a Federal Pen, I got to know Frondizi, the art forger they'd put away for those Modiglianis, remember? And he'd gotten it somehow; and he was ready to turn it into a little nest egg for his twilight years, y'know? So I made a deal with him, got the Enquirer interested because of the lost tomb angle..."

Yaffa said, "Tell me of the tomb."

Loder held his pipe and the reins in one hand and, with difficulty and a pipe nail, cleaned the dottle from the bowl.

"The glyph is a funerary seal. It came off a sarcophagus. Hittite. We think. Maybe not. Maybe older. No way of knowing because the inscriptions are beyond us. But the Subhi Pasha's man was very precise as to where the tomb was located." He pointed above them. "Up there somewhere, above Mamoula."

"And the glowing of the stone?" Yaffa demanded.

"We didn't know about that," Bobby Shafka said. "It didn't start till the night you found us."

Yaffa was silent for a time, then said, "I think you are two very foolish men." He spurred the pony and pulled ahead of them, saying over his shoulder, "And I am the most foolish of all." He fell in behind the guides.

They were approaching 6500 feet, and mist began to lattice their passage.

"There's something I've never told you, that I ought to tell you."

"Why tell me now?"

"Who knows what the hell can happen. I've been riding scared these last last few days. When those guys from Mamoula saw this valley..."

"Not valley. This is a meander belt: part of an old flood plain. Very uncommon at this altitude."

"Whatever. When they came out of the pass and saw this, and they wouldn't come down, and they took off...well, who the hell knows what can happen. And I just wanted to tell you something I never told you."

"Which is—?"

"You gonna be able to handle it?"

"Bobby! For pete's sake, get on with it already!"

"I'm gay. Always have been."

"That's your big secret?"

"Well...pretty big secret, yeah. My mother never even knew. That's it, anyway. What, you don't think that's something important enough to tell your best friend?"

"Bobby, I've known you're homosexual since we were fifteen."

"You have?"

"What do you think, I'm smart enough to be the one person you picked for this lunatic trip, but I'm not smart enough to know you're gay. Truly, Bobby, I wouldn't sell you that short."

"Man, I hope I don't have to say I'm sorry we pulled this caper. That stuff in the Subhi Pasha's papers about 'losing your immortal soul' scares the crap outta me!"

"Little late for you to be getting religion, isn't it?"

"Well, you know...when you spend your life in the closet, and every time some asshole talks about faggots and pooftas, you just get to believe you're going to Hell, and you sort of give religion a pass. But what d'ya think, there's something to it? We could be going into someplace we ought not, what d'ya think?"

Loder drew on his pipe, put the little gold reflector over the mouth of the bowl, and sent a cloud of smoke toward the evening sky. "What I think, pal, is that it's not just a little, it's a lot too late to be worrying about it."

He pointed to the meander belt below where they had camped on a cusp; to the low central hill encircled by the stream. "That's the core. When we go down there, and we dig, I think we're going to find it's a burial mound. And I think we're going to find something no one has ever seen. And I think we're going to have one deuce of a time lugging it out of here and down these mountains. And I think we should have been better prepared, and maybe had a helicopter standing by, to get us out of here. And I think a whole lot of things, Bobby. But about losing 'my immortal soul,' well, it's too late for us to try to buy into God's good graces."

Night fell suddenly, and it grew cool enough to come out in the open, and Yaffa found them, and led them down to the meander core, taking with them only the pony carrying water and digging gear. And as they neared the central hill, Bobby Shafka looked at his friend, about to say something from their childhood; and he saw the glyph glowing in Loder's vest pocket; and he was frightened at his impertinence, thinking he could pull this off. Just one more harebrained scheme. A

nd this time, lost up here in a valley filling with mist, following a hundred-year-old line of bullshit, he had finally bet too much. This time, he was sure, he was going to take Dennis down with him...and that was that for their immortal souls.

The wind rose. The wind that blows forever between the stars, carrying ancient and encoded messages of indecipherable night. And darkness upon the face of the deep.

The ground split. The glyph became unbearably bright, and the earth split. Yaffa had gone. One moment he was there, beside them and a moment later...gone. He had not abandoned them; they never thought that for an instant. He had done what any sensible man would do: he had gotten out while he could. There were those who depended on him, he'd said so. And they were alone with the sarcophagus.

The glyph had shone so brightly, through the heavy duck of Loder's thermal vest, that he had pulled it out, and averted his eyes lest he go blind. Yes, staring into the sun.

For no reason he could name—no more reason than that which told him he and Bobby Shafka had brought the stone seal home—he laid the glyph on the mound. And the earth split.

They went down the ancient steps carved in the stone, and came to the entrance to the portal. It stood open. When the earth had split, it had made itself an open way.

They needed no flashlights. The glyph illuminated the hewn stone walls of the passage that descended at a shallow angle beneath the meander belt. And far below, ahead of them, lay the sarcophagus. Now they knew, without question.

"If you mention immortal souls one more time," Dennis said tightly, and he ground his teeth, "I will do you in myself."

And they came to the great chamber where the sarcophagus lay.

It was large, but not beautiful. Stone box and lid, deeply etched with inscriptions, and a frieze of kings and servants.

Loder bent over the casket and said nothing. He ran.his hands over the surface, and looked more closely. Once, he motioned Bobby to him, and pointed to the fractured sigil niche where the glyph had been positioned. "I don't think it was there when they buried this," Dennis said.

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

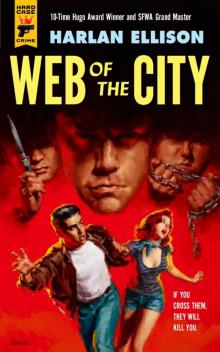

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage