- Home

- Harlan Ellison

Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions Read online

* * *

Fictionwise Publications

www.fictionwise.com

Copyright (C)1964 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, copyright (C) 1992 by Harlan Ellison. All rights reserved.

* * *

NOTICE: This work is copyrighted. It is licensed only for use by the purchaser. Making copies of this work or distributing it to any unauthorized person by any means, including without limit email, floppy disk, file transfer, paper print out, or any other method constitutes a violation of International copyright law and subjects the violator to severe fines. Fictionwise offers a reward of up to $500 for information leading to the conviction of any person violating the copyright of a Fictionwise ebook.

* * *

Tears were impossible, yet tears were his heritage. Sorrow was beyond him, yet sorrow was his birthright. Anguish was denied him; even so, anguish was his stock in trade. For Trente, there was no unhappiness; nor was there joy, concern, discomfort, age, time, feeling.

And this was as the Ethos had planned it.

For Trente had been appointed by the Ethos—the race of somewhere/somewhen beings who morally and ethically ruled the universes—as their Paingod. To Trente, who knew neither the tug of time nor the crippling demands of the emotions, fell the forever task of dispensing pain and sorrow to the myriad multitudes of creatures that inhabited the universes. Whether sentient or barely capable of the feeblest unicellular reaction-formation, Trente passed along from his faceted cubicle invisible against the backdrop of the changing stars, unhappiness and misery in proportions too complexly arrived at to be verbalized.

He was Paingod for the universes, the one who dealt out the tears and the anguish and the soul-wrenching terrors that blighted life from its first moment to its last. Beyond age, beyond death, beyond feeling—lonely and alone in his cubicle—Trente went about his business without concern or pause.

Trente was not the first Paingod; there had been others. They had come before, not too many of them, but a few, and why they no longer held their post was a question Trente had never asked. He was the chosen one from a race that lived almost indefinitely, and his job was to pass along the calibrated and measured dollops of melancholy as prescribed by the Ethos. It involved no feeling and no concern, only attention to duty. It was his position, and it was his obligation. How peculiar it was that he felt concern, after all this time.

It had begun so long before—and of time he had no conception—that the only marking date with validity was that in the great ocean soon to become the Gobi Desert, paramecia had become more prevalent than amoebae. It had grown in him through the centimetered centuries as layers and layers of forever settled down like mist to form the strata of the past.

Now, it was now.

* * * *

Despite the strange ache in his nerve-gland, his central nerve-gland; despite the progressive dulling of his eye globes; despite the mad thoughts that spat and stuttered through his triple-domed cerebrum, thoughts of which he knew he was incapable; despite all this, Trente performed his now functions as he was required:

He dispensed unbearable anguish to the residents of a third-power planet in the Snail Cluster, supportable agony to a farm colony that had sprung up on Jacopettii U, incredible suffering to a parentless spider-child on Hiydyg IX, and relentless torment to a blameless race of mute aborigines on a nameless, arid planet circling a dying sun of the 707 System.

And through it all, Trente suffered for his charges.

What could not be, was. What could not come to pass, had. The soulless, emotionless, regimented creature that the Ethos had named Paingod had contracted a sickness. Concern. At last, after centuries too filed away to unearth and codify, Trente had reached a Now in which he could no longer support his acts. He cared.

The physical manifestations of his mental upheaval were numerous. His oblong head throbbed and his eye globes were dulling, a little more each decade; the interlinked duodenal ulcers so necessary to his endocrinal system's normal function had begun to misfire like faulty plugs in an old car; the thwack! of his salamander tail had grown weaker, indicating his motor responses to nerve endings were feebler. Trente—who had always been considered rather a handsome example of his race—had slowly come to look forlorn, weary, even a touch pathetic.

And he sent down woe to an armored, flying creature with a mite-sized brain on a dark planet at the edge of the Coalsack; he dispatched fear and trembling to a smokelike wraith that was the only visible remains of a great race that had learned to dispense with its bodies centuries before, in the sun known as Vertel; he conscientiously winged terror and unhappiness and misery and sadness to a group of murdering pirates, a clique of shrewd politicians and a brothelful of unregenerate whores—all on a fifth-power planet of the White Horse Constellation.

Stopped alone there, in the night of space, his mind spiraling now for the first time down a strange and disquieting chamber of thought, Trente twisted within himself. I was selected because I lacked the certain difficulties I now manifest. What is this torment? What is this unpleasant, unhappy, unrelenting feeling that gnaws at me, tears at me, corrupts my thoughts, colors darkly my every desire? Am I going mad? Madness is beyond my race; it is a something we have never known. Have I been at this post too long, have I failed in my duties? If there was a God stronger than the God that I am, or a God stronger than the Ethos Gods, then I would appeal to that God. But there is only silence and the night and the stars, and I'm alone, so alone, so God all alone here, doing what I must, doing my best.

And then, finally: I must know. I must know!

...while he spun a fiber of melancholy down to a double-thoraxed insect-creature on Io, speared with dread a blob of barely sentient mud on Acaras III, pain-goaded into suicide an electrical wave-being capable of producing exquisite fifteen-toned harmonics on Syndon Beta V, reduced by half the pleasures of a pitiable slug thing in the methane caves of Kkklll IV, enshrouded in bitterness and misery a man named Colin Marshack on an insignificant planet called Sol III, Earth, Terra, the world...

And then, finally: I will know. I will know!

Trente removed the scale model of Earth from the display crate, and stared at it. Such a tiny thing, such a helpless thing, to support the nightwalk of a Paingod.

He selected the most recent recipient of his attentions, through no more involved method than that, and used the means of travel his race had long since perfected to leave his encased cubicle hanging translucent against the stars. Trente, Paingod of the universes, for the first time in all the centuries he had lived that life of giving, never receiving, left his place, and left his Now, and went to find out. To find out ... what? He had no way of knowing.

For the Paingod, it was the first nightwalk.

* * * *

Pieter Koslek had been born in a dwarf province of a minuscule Central European country long since swallowed up by a tiny power now a member of the Common Market. He had left Europe early in the 1920s, had shipped aboard a freighter to Bolivia and, after working his way as common deckhand and laborer through half a dozen banana republics, had been washed up on an inland shore of the United States in 1934. He had promptly gone to earth, gone to seed, and gone to fat. A short stint in a CCC camp, a shorter stint as a bouncer in a Kansas City speak, a term in the Illinois State Workhouse, a long run on the Pontiac assembly line making an obscure part for an obscure segment of a B-17's innards, a brief fling as owner of a raspberry farm, and an extended period as a skid row-frequenting wino summed up his life. Now, as now would be reckoned by any sane man's ephemeris, Pieter Koslek was a wetbrain—an alcoholic so sunk in the fumes and vapors of his own liquor need that he was barely recognizable as a human being. Lying soddenly, but quietly, in an a

lley two blocks up from the Greyhound bus station in downtown Los Angeles, Pieter Koslek, age fifty-nine, weight 210, hair filth gray, eyes red and moist and closed, unceremoniously died. That simply, that unconcernedly, that uneventfully for all the young-old men in overlong GI surplus overcoats who passed by that alley mouth unseeing, uncaring—Pieter Koslek died. His brain gave out, his lungs ceased to bellow, his heart refused to pump, his blood slid to a halt in his veins, and breath no longer passed his lips. He died. End of story, beginning of story. As he lay there, half-propped against the brick wall with its shredded reminder of a lightweight boxing match between two stumblebums long since passed into obscurity and the files of Ring Magazine, a thin tepid vapor of pale green came to the useless body of Pieter Koslek; touched it; felt of it; entered it; Trente was on the planet Earth, Sol III.

If it had been possible to mount an epitaph on bronze for the wetbrain, there on the wall of the alley perhaps, the most fitting would have been: HERE LAY PIETER KOSLEK. NOTHING IN HIS LIFE BECAME HIM SO MUCH AS THE LEAVING OF IT.

* * * *

The thick-bodied orator on the empty packing crate had gathered a sizable crowd. His license was encased in plastic, and it had been pinned to a broom handle sharpened and driven into the ground. An American flag hung limply from a pole on the other side of the makeshift podium. The flag had only forty-eight stars; it had been purchased long before Hawaii or Alaska had joined the union, but new flags cost money, and—

“Scum! Like sewer water poured into your bloodstream! Look at them, do they look like you, do they smell like you—those smells, those, those stinks that walk like men! That's what they are, stinks with voting privileges, all of them, the niggers, the kike-jews who own the land and the apartments you live in, what they think they're big deals! The spics, the Puerto Rican filth that takes over your streets and rapes your women and puts its lousy hands on your white young daughters, that scum...”

Colin Marshack stood in the crowd, staring up at the thick-bodied orator, his shaking hands thrust deep into his sport jacket pockets, his head throbbing, the unlit cigarette hanging unnoticed from his lips. Every word.

“...Commies in public office, is what we have got to be content with. Nigger lovers and pawns of the kike bastards who own the corporations. They wanta kill all of you, all of us, every one of us. They want us to say, ‘Hey! C'mon, make love to my sister, to my wife, do all the dirty things that'll pollute my pure race!’ That's what the Commies in public office, misusing our public trust, say to us. And what do we say in return, back to them, we say, ‘No dice, dirty spics, lousy kikes, Puerto bastards, black men that want to steal our pure heritage!’ We say, go to hell to them, go straight to hell, you dirty rotten sonsuh—”

At which point the policemen moved quietly through the crowd, fascinated and silent like cobras at a mongoose convention, and arrested the thick-bodied orator.

As they took him away, Colin Marshack turned and moved out of the milling group. Why is such hideousness allowed to exist, he thought bitterly, fearfully. He walked down the path and out of Pershing Square ("Pershing Square is where they have a fence up so the fruits can't pick the people.") and did not even realize the rheumy-eyed old man was following him till he was six blocks away.

Then he turned, and the old man almost ran into him. “Something I can do for you?” Colin Marshack asked.

The old man grinned feebly, his pale gums exposing themselves above gap-toothed ruin. “Nosir, nuh-nosir, I just, uh, I was just follerin’ along to see maybe I could tap yah for a couple cents ’tuh get some chick'n noodle soup. It's kinda cold ... ’n I thought, maybe...”

Colin Marshack's wide, somehow humorous face settled into understanding lines. “You're right, old man, it's cold, and it's windy, and it's miserable, and I think you're entitled to some goddam chicken noodle soup. God knows someone's entitled.” He paused a beat, added, “Maybe me.”

He took the old man by the arm, seemingly unaware of the rancid, rotting condition of the cloth. They walked along the street outside the park, and turned into one of the many side routes littered with one-arm beaneries and 40¥-a-night flophouses.

“And possibly a hot roast beef sandwich with gravy all over the french fries,” Colin added, steering the wine-smelling old derelict into a restaurant.

Over coffee and a bear claw, Colin Marshack stared at the old man. “Hey, what's your name?”

“Pieter Koslek,” the old man murmured, hot vapors from the thick white coffee mug rising up before his watery eyes. “I've, uh, been kinda sick, y'know...”

“Too much sauce, old man,” said Colin Marshack. “Too much sauce does it for a lot of us. My father and mother both. Nice folk, loved each other, they went to the old alky's home hand in hand. It was touching.”

“You're kinda feelin’ sorry for y'self, ain'tcha?” said Pieter Koslek. And looked down at his coffee hurriedly.

Colin stared across angrily. Had he sunk that low, that quickly, that even the seediest cockroach-ridden bum in the gutter could snipe at him, talk up to him, see his sad and sorry state? He tried to lift his coffee cup, and the cream-laced liquid sloshed over the rim, over his wrist. He yipped and set the cup down quickly.

“Your hands shake worse'n mine, mister,” Pieter Koslek noted. It was a curious tone, somehow devoid of feeling or concern—more a statement of observation.

“Yeah, my hands shake, Mr. Koslek, sir. They shake because I make my living cutting things out of stone, and for the past two years I've been unable to get anything from stone but tidy piles of rock dust.”

Koslek spoke around a mouthful of cruller. “You, uh, you're one'a them statue makers, what I mean a sculpt'r.”

“That is precisely what I am, Mr. Koslek, sir. I am a capturer of exquisite beauty in rock and plaster and quartz and marble. The only trouble is, I'm no damned good, and I was never ever really very good, but at least I made a decent living selling a piece here and there, and conning myself into thinking I was great and building a career, and Canaday in the Times said a few nice things about me. But even that's turned to rust now. I can't make a chisel do what I want it to do, I can't sand and I can't chip and I can't carve dirty words on sidewalks if I try.”

Pieter Koslek stared across at Colin Marshack, and there was a banked fire down in those rheumy, sad old eyes. He watched and looked and saw the hands shaking uncontrollably, saw them wring one against another like mad things, and even when interlocked, they still trembled hideously.

And...

Trente, locked within an alien shell, comprehended a small something. This creature of puny carbon atoms and other substances that could not exist for an instant in the rigorous arena of space, was dying. Inside, it was ending its life cycle, because of the misery Trente had sent down. Trente had been responsible for the quivering pain that sent Colin Marshack's hands into spasms. It had been done two years before—by Colin Marshack's time—but only a few moments earlier as Trente knew it. And now it had changed this creature's life totally. Trente watched the strange human being, a product of little introverted needs and desires. And he knew he must go farther, must experiment further with his problem. The green and transparent vapor that was Trente seeped out of the eyes of Pieter Koslek, and slid carefully inside Colin Marshack. It left itself wide open, flung itself wide open, to what tremors governed the man. And Trente felt the full impact of the pain he so lightly dispensed to all the living things in the universes. It was potent hot all! And it was a further knowing, a greater knowledge, a simple act that the sickness had compelled him to undertake. By the fear and the memory of all the fears that had gone before, Trente knew, and knowing, had to go farther. For he was Paingod, not a transient tourist in the country of pain. He drew forth the mind of Marshack, of that weak and trembling Colin Marshack, and fled with it. Out. Out there. Farther. Much farther. Till time came to a slithering halt and space was no longer of any consequence. And he whirled Colin Marshack through the universes. Through the infinite allness of the space and t

ime and motion and meaning that was the crevice into which Life had sunk itself. He saw the blobs of mud and the whirling winged things and the tall humanoids and the cleat-treaded half-men/half-machines that ruled one and another sector of open space. He showed it all to Colin Marshack, drenched him in wonder, filled him like the most vital goblet the Ethos had ever created, poured him full of love and life and the staggering beauty of the cosmos. And having done that, he whirled the soul and spirit of Colin Marshack down down and down to the fibrous shell that was his body, and poured that soul back inside. Then he walked the shell to the home of Colin Marshack ... and turned it loose. And...

* * * *

When the sculptor awoke, lying face down amidst the marble chips and powder-fine dust of the statue, he saw the base first; and not having recalled even buying a chunk of stone that large, raised himself on his hands, and his knees, and his haunches, and sat there, and his eyes went up toward the summit, and seemed to go on forever, and when he finally saw what it was he had created—this thing of such incredible loveliness and meaning and wisdom—he began to sob. Softly, never very loud, but deeply, as though each whimper was drawn from the very core of him.

He had done it this once, but as he saw his hands still trembling, still murmuring to themselves in spasms, he knew it was the one time he would ever do it. There was no memory of how, or why, or even of when ... but it was his work, of that he was certain. The pain in his wrists told him it was.

The moment of truth stood high above him, resplendent in marble, but there would be no other moments.

This was Colin Marshack's life, in its totality, now.

The sound of sobbing was only broken periodically, as he began to drink.

* * * *

Waiting. The Ethos waited. Trente had known they would. It was inevitable. Foolish for him to conceive of a situation of which they would not have an awareness.

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

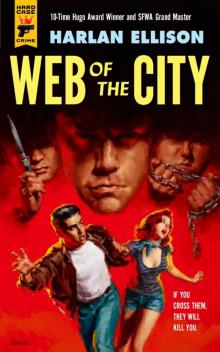

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage