- Home

- Harlan Ellison

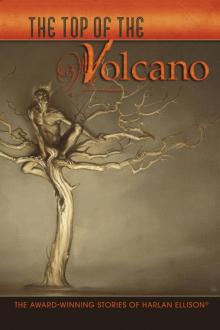

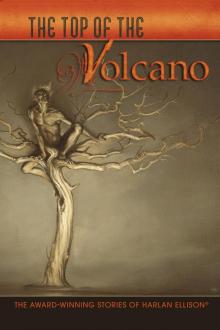

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Read online

THE TOP OF THE VOLCANO

THE AWARD-WINNING STORIES OF HARLAN ELLISON®

is an Edgeworks Abbey® Offering in association with Subterranean Press.

Published by arrangement with the Author and The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

THE TOP OF THE VOLCANO

THE AWARD-WINNING STORIES OF HARLAN ELLISON®

by Harlan Ellison®

This edition is copyright © 2014 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

All rights reserved.

Harlan Ellison and Edgeworks Abbey

are registered trademarks of The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

Dust jacket illustration Copyright © 2013 by Michael Whelan.

All rights reserved.

Print version interior design Copyright © 2014 by Desert Isle Design, LLC.

All rights reserved.

“The Region Between” art and graphic design by Jack Gaughan.

Electronic Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-635-9

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical—including photocopy, recording, Internet posting, electronic bulletin board—or any other information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a critical article or review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper, or electronically transmitted on radio, television or in a recognized on-line journal. For information address Author’s agent: Richard Curtis Associates, Inc., 171 East 74th Street, New York, New York 10021, USA.

All persons, places and organizations in this book—except those clearly in the public domain—are fictitious and any resemblance that may seem to exist to actual persons, places or organizations living, dead or defunct is purely coincidental. These are works of fiction.

Harlan Ellison websites:

www.harlanellison.com

www.harlanbooks.com

Subterranean Press:

subterraneanpress.com

PO Box 190106, Burton, MI 48519

“‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman,” copyright © 1965 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1993 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” copyright © 1967 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1995 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World,” copyright © 1968 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1996 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“A Boy and His Dog,” copyright © 1969 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1997 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Region Between,” copyright © 1969 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1997 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation. Design and Graphics by Jack Gaughan. Copyright © 1969 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 1997 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Basilisk,” copyright © 1972 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2000 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Deathbird,” copyright © 1973 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2001 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” copyright © 1973 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2001 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans: Latitude 38° 54' N, Longitude 77° 00' 13" W,” copyright © 1974 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2002 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Croatoan,” copyright © 1975 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2003 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Jeffty Is Five,” copyright © 1977 by Harlan Ellison. Renewed, 2005 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Count the Clock That Tells the Time,” copyright © 1978 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Djinn, No Chaser,” copyright © 1982 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Paladin of the Lost Hour,” copyright © 1985, 1986 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“With Virgil Oddum at the East Pole,” copyright © 1984 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Soft Monkey,” copyright © 1987 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Eidolons,” copyright © 1988 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Function of Dream Sleep,” copyright © 1988 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” copyright © 1991 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Mefisto in Onyx,” copyright © 1993 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“Chatting with Anubis,” copyright © 1995 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

“The Human Operators” with A.E. van Vogt, copyright © 1970 by Harlan Ellison and A.E. van Vogt. Renewed, 1998 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation and A.E. van Vogt.

“How Interesting: A Tiny Man,” copyright © 2009 by The Kilimanjaro Corporation.

* * *

Contents

‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream

The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World

A Boy and His Dog

The Region Between

Basilisk

The Deathbird

The Whimper of Whipped Dogs

Adrift Just Off the Islets of Langerhans:

Latitude 38° 54' N, Longitude 77° 00' 13" W

Croatoan

Jeffty is Five

Count the Clock That Tells the Time

Djinn, No Chaser

Paladin of the Lost Hour

With Virgil Oddum at the East Pole

Soft Monkey

Eidolons

The Function of Dream Sleep

The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore

Mefisto in Onyx

Chatting with Anubis

The Human Operators with A.E. van Vogt

How Interesting: A Tiny Man

* * *

“Repent, Harlequin!” Said the Ticktockman

1966 Hugo Award: Best Short Fiction; Nebula Award: Best Short Story

There are always those who ask, what is it all about? For those who need to ask, for those who need points sharply made, who need to know “where it’s at,” this:

The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies. They are the standing army, and the militia, jailors, constables, posse comitatus, etc. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw or a lump of dirt. They have the same sort of worth only as horses and dogs. Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others—as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and officeholders—serve the state chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the Devil, without intending it, as God. A very few, as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men, serve the state with their consciences also, and so necessarily resist it for the most part; and they are commonly treated as enemies by it.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

That is the heart of it. Now begin in the middle, and later learn the beginning; the end will take care of itself.

But because it was the very world it was, the very world they had allowed it to become, for months his activities did not come to the alarmed attention of The Ones Who Kept The Machine Functioning Smoothly, the ones who poured the very best butter over the cams and mainsprings of the culture. Not until it had become obvious that somehow, someway, he had become a notoriety, a celebrity, perhaps even a hero for (w

hat Officialdom inescapably tagged) “an emotionally disturbed segment of the populace,” did they turn it over to the Ticktockman and his legal machinery. But by then, because it was the very world it was, and they had no way to predict he would happen—possibly a strain of disease long-defunct, now, suddenly, reborn in a system where immunity had been forgotten, had lapsed—he had been allowed to become too real. Now he had form and substance.

He had become a personality, something they had filtered out of the system many decades before. But there it was, and there he was, a very definitely imposing personality. In certain circles—middle-class circles—it was thought disgusting. Vulgar ostentation. Anarchistic. Shameful. In others, there was only sniggering: those strata where thought is subjugated to form and ritual, niceties, proprieties. But down below, ah, down below, where the people always needed their saints and sinners, their bread and circuses, their heroes and villains, he was considered a Bolivar; a Napoleon; a Robin Hood; a Dick Bong (Ace of Aces); a Jesus; a Jomo Kenyatta.

And at the top—where, like socially-attuned Shipwreck Kellys, every tremor and vibration threatening to dislodge the wealthy, powerful and titled from their flagpoles—he was considered a menace; a heretic; a rebel; a disgrace; a peril. He was known down the line, to the very heartmeat core, but the important reactions were high above and far below. At the very top, at the very bottom.

So his file was turned over, along with his time-card and his cardioplate, to the office of the Ticktockman.

The Ticktockman: very much over six feet tall, often silent, a soft purring man when things went timewise. The Ticktockman.

Even in the cubicles of the hierarchy, where fear was generated, seldom suffered, he was called the Ticktockman. But no one called him that to his mask.

You don’t call a man a hated name, not when that man, behind his mask, is capable of revoking the minutes, the hours, the days and nights, the years of your life. He was called the Master Timekeeper to his mask. It was safer that way.

“This is what he is,” said the Ticktockman with genuine softness, “but not who he is. This time-card I’m holding in my left hand has a name on it, but it is the name of what he is, not who he is. The cardioplate here in my right hand is also named, but not whom named, merely what named. Before I can exercise proper revocation, I have to know who this what is.”

To his staff, all the ferrets, all the loggers, all the finks, all the commex, even the mineez, he said, “Who is this Harlequin?”

He was not purring smoothly. Timewise, it was jangle.

However, it was the longest speech they had ever heard him utter at one time, the staff, the ferrets, the loggers, the finks, the commex, but not the mineez, who usually weren’t around to know, in any case. But even they scurried to find out.

Who is the Harlequin?

High above the third level of the city, he crouched on the humming aluminum-frame platform of the air-boat (foof! air-boat, indeed! swizzleskid is what it was, with a tow-rack jerry-rigged) and he stared down at the neat Mondrian arrangement of the buildings.

Somewhere nearby, he could hear the metronomic left-right-left of the 2:47 pm shift, entering the Timkin roller-bearing plant in their sneakers. A minute later, precisely, he heard the softer right-left-right of the 5:00 am formation, going home.

An elfin grin spread across his tanned features, and his dimples appeared for a moment. Then, scratching at his thatch of auburn hair, he shrugged within his motley, as though girding himself for what came next, and threw the joystick forward, and bent into the wind as the air-boat dropped. He skimmed over a slidewalk, purposely dropping a few feet to crease the tassels of the ladies of fashion, and—inserting thumbs in large ears—he stuck out his tongue, rolled his eyes, and went wugga-wugga-wugga. It was a minor diversion. One pedestrian skittered and tumbled, sending parcels everywhichway, another wet herself, a third keeled slantwise and the walk was stopped automatically by the servitors till she could be resuscitated. It was a minor diversion.

Then he swirled away on a vagrant breeze, and was gone. Hi-ho. As he rounded the cornice of the Time-Motion Study Building, he saw the shift, just boarding the slidewalk. With practiced motion and an absolute conservation of movement, they sidestepped up onto the slow-strip and (in a chorus line reminiscent of a Busby Berkeley film of the antediluvian 1930s) advanced across the strips ostrich-walking till they were lined up on the expresstrip.

Once more, in anticipation, the elfin grin spread, and there was a tooth missing back there on the left side. He dipped, skimmed, and swooped over them; and then, scrunching about on the air-boat, he released the holding pins that fastened shut the ends of the home-made pouring troughs that kept his cargo from dumping prematurely. And as he pulled the trough-pins, the air-boat slid over the factory workers and one hundred and fifty thousand dollars’ worth of jelly beans cascaded down on the expresstrip.

Jelly beans! Millions and billions of purples and yellows and greens and licorice and grape and raspberry and mint and round and smooth and crunchy outside and soft-mealy inside and sugary and bouncing jouncing tumbling clittering clattering skittering fell on the heads and shoulders and hardhats and carapaces of the Timkin workers, tinkling on the slidewalk and bouncing away and rolling about underfoot and filling the sky on their way down with all the colors of joy and childhood and holidays, coming down in a steady rain, a solid wash, a torrent of color and sweetness out of the sky from above, and entering a universe of sanity and metronomic order with quite-mad coocoo newness. Jelly beans!

The shift workers howled and laughed and were pelted, and broke ranks, and the jelly beans managed to work their way into the mechanism of the slidewalks after which there was a hideous scraping as the sound of a million fingernails rasped down a quarter of a million blackboards, followed by a coughing and a sputtering, and then the slidewalks all stopped and everyone was dumped thisawayandthataway in a jackstraw tumble, still laughing and popping little jelly bean eggs of childish color into their mouths. It was a holiday, and a jollity, an absolute insanity, a giggle. But…

The shift was delayed seven minutes.

They did not get home for seven minutes.

The master schedule was thrown off by seven minutes.

Quotas were delayed by inoperative slidewalks for seven minutes.

He had tapped the first domino in the line, and one after another, like chik chik chik, the others had fallen.

The System had been seven minutes’ worth of disrupted. It was a tiny matter, one hardly worthy of note, but in a society where the single driving force was order and unity and equality and promptness and clocklike precision and attention to the clock, reverence of the gods of the passage of time, it was a disaster of major importance.

So he was ordered to appear before the Ticktockman. It was broadcast across every channel of the communications web. He was ordered to be there at 7:00 dammit on time. And they waited, and they waited, but he didn’t show up till almost ten-thirty, at which time he merely sang a little song about moonlight in a place no one had ever heard of, called Vermont, and vanished again. But they had all been waiting since seven, and it wrecked hell with their schedules. So the question remained: Who is the Harlequin?

But the unasked question (more important of the two) was: how did we get into this position, where a laughing, irresponsible japer of jabberwocky and jive could disrupt our entire economic and cultural life with a hundred and fifty thousand dollars’ worth of jelly beans…

Jelly for God’s sake beans! This is madness! Where did he get the money to buy a hundred and fifty thousand dollars’ worth of jelly beans? (They knew it would have cost that much, because they had a team of Situation Analysts pulled off another assignment, and rushed to the slidewalk scene to sweep up and count the candies, and produce findings, which disrupted their schedules and threw their entire branch at least a day behind.) Jelly beans! Jelly…beans? Now wait a second—a second accounted for—no one has manufactured jelly beans for over a hundred years. Where

did he get jelly beans?

That’s another good question. More than likely it will never be answered to your complete satisfaction. But then, how many questions ever are?

The middle you know. Here is the beginning. How it starts:

A desk pad. Day for day, and turn each day. 9:00—open the mail. 9:45—appointment with planning commission board. 10:30—discuss installation progress charts with J.L. 11:45—pray for rain. 12:00—lunch. And so it goes.

“I’m sorry, Miss Grant, but the time for interviews was set at 2:30, and it’s almost five now. I’m sorry you’re late, but those are the rules. You’ll have to wait till next year to submit application for this college again.” And so it goes.

The 10:10 local stops at Cresthaven, Galesville, Tonawanda Junction, Selby, and Farnhurst, but not at Indiana City, Lucasville and Colton, except on Sunday. The 10:35 express stops at Galesville, Selby, and Indiana City, except on Sundays & Holidays, at which time it stops at…and so it goes.

“I couldn’t wait, Fred. I had to be at Pierre Cartain’s by 3:00, and you said you’d meet me under the clock in the terminal at 2:45, and you weren’t there, so I had to go on. You’re always late, Fred. If you’d been there, we could have sewed it up together, but as it was, well, I took the order alone…” And so it goes.

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Atterley: In reference to your son Gerold’s constant tardiness, I am afraid we will have to suspend him from school unless some more reliable method can be instituted guaranteeing he will arrive at his classes on time. Granted he is an exemplary student, and his marks are high, his constant flouting of the schedules of this school makes it impractical to maintain him in a system where the other children seem capable of getting where they are supposed to be on time and so it goes.

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage