- Home

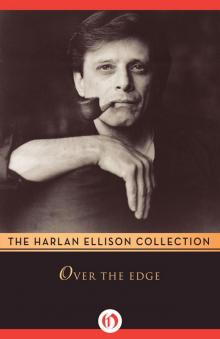

- Harlan Ellison

Angry Candy Page 7

Angry Candy Read online

Page 7

She had no idea what he was saying. She had always known she was alone. That was simply the way it was. Not the foolish concept of loneliness of Sartre or Camus, but alone, all alone in a universe that would kill her if it knew she existed.

"Yes," he said, "and that's why I have to do something about you. If you are the last of your kind, then this life of chances, just to satisfy your needs, must end."

"You're going to kill me. Then do it quickly. I always knew that would happen. Just do it fast, you weird son of a bitch."

He had read her thoughts.

"Don't be a fool. I know it's hard not to be paranoid; what you've been all your life programs that into you. But don't be a fool if you can stop. There's nothing of survival in stupidity. That's why so many of the last of their kind are gone."

"What the hell are you?!?" she demanded to know.

He smiled and offered her the tray of vegetables.

"You're a carrot, a goddam carrot!" she yelled.

"Not quite," said the voice in her head. "But from a different mother and father than you; from a different mother and father than everyone else out on the streets of Paris tonight. And neither of us will die."

"Why do you want to protect me?"

"The last save the last. It's simple."

"For what? For what will you protect me?"

"For yourself. . . for me."

He began to remove his clothes. Now, in the blue light, she could see that he was very pale, not quite the shade that facial makeup had lent him; not quite white. Perhaps the faintest green tinge surging along under the firm, hard skin.

In all other respects, and superbly constructed, he was human; and tumescently male. She felt herself responding to his nakedness.

He came to her and carefully, slowly — because she did not resist — he removed her clothes; and she realized that she was Claire again, not the matted-fur child of the night. When had she changed back?

It was all happening without her control.

Since the time a very long time ago when she had gone on her own, she had controlled. Her life, the lives of those she met, her destiny. But now she was helpless, and she didn't mind giving over control to him. Fear had drained out of her, and something quicker had replaced it.

When they were both naked, he drew her down onto the carpet and began to make slow, careful love to her. In the planter box above them she thought she could detect the movement of the hearty green things trembling slightly, aching toward them and the power they released as they spasmed together in a ritual at once utterly new because theirs was the meeting of the unfamiliar, yet ancient as the moon.

And as the shadow of passion closed around her she heard him whisper, "There are many things to eat."

For the first time in her life, she could not hear the sound of footsteps following her.

SIXTY FEET ABOVE the smooth surface of the North Atlantic, next to the forward rail of the Titanic's main deck, a rippling slit opened in the darkness of the night. A scintillant orange mist swirled through the slit, and the three Time Commandos stepped through onto the deck of the luxury liner.

Even before he had emerged completely from riptime Sgt. Ratliff was complaining. "Why me? Why is it always me? Why the hell don't one of you smartapples ever volunteer? Just once! Why's it always me has to do the dangerous stuff?"

It was 11:27 P.M. on April 14, 1912. The orange mist sucked itself back into the slit, the egress into riptime vanished, and the raiding patrol from the far future stood in the darkness.

The Titanic rode a surface of saintly calm. That millennium's Oberstgruppenführer of Time Commandos, "Blackjack" Alec de la Ree, fished among the shaped charges in a bandolier pocket, came up with a nasty stub of cigar, wetted it and wedged it in the left corner of his mouth. "Because, Ratlips," he said, grinding Ratliff's gears with the hated nickname, "you know damned well you've got the highest probability distribution quotient of anybody on the team." The words probability, distribution, and quotient were almost unintelligible around the cigar butt. He lit up with a wooden kitchen match endemic to the phenomenological year in which this raid was being staged. "Just once is there a chance we can pull off a patrol without you piss and moan? Try to fix your pea-brain on the idea, Sergeant: we're here in service of humanity! Bernoulli equations picked you, chum, not us. You're the one stays behind so the rest of us get back through riptime. That's what you draw your pay for."

The third Time Commando, Corporal Cicero, chimed in with agreement and annoyance that Ratliff was sturmdranging again. "You're a fast pain in the fundament, y'know that?"

"Okay, okay," Ratliff said. "But I'm gonna register a beef when we get back to Chronobase."

"Let's just correct this node in the Phenom Flow, save the future again, and go home," de la Ree said. "Then you can squeal all you want."

He glanced down at the fingernail of his left thumb, where the subjective hour of this year in the Phenom Flow strobed crimson in digital readout. They were crossing the Grand Banks. "It's eleven-forty their time." He stared off the starboard bow. "There it is!"

A gigantic, menacing hulk of ice loomed up fifty feet from the flat surface of the sea.

"Move fast!" de la Ree hissed. The trio of Time Commandos rushed to complete their assigned tasks. Within two minutes they were back at the bow rail.

"Everything set?" de la Ree asked. The cigar was out; he was winded from his activities. Ratliff and Cicero nodded it was all set. De la Ree smiled. "In thirty seconds the future'll be set right, humanity'll be okay for another thousand years, and we get some relief time."

He opened the slit into riptime, shooed Cicero into the pulsing orange mist, and took a step toward the egress. "I still think it's chicken-doo," Ratliff said. "What if I get caught in the Flow?"

De la Ree gave him one last look of disgust as he relit the cigar stub, blew a cloud of noxious smoke at the noncom, and said, "Up yours, Ratlips. Just save humanity and we'll see ya at Chronobase." As he placed one foot into the mist, he looked back and added, "An' try not to drag a decade along with ya, y'wanna listen to me?" Then he was gone.

At that moment, still doing twenty-two knots, the great liner began slipping to port as the First Officer yelled to the Wheelman that a berg was drifting in on their starboard side. The Wheelman reacted instantly. The ship slid slowly toward safety.

So Ratlips ensured the future of humanity by triggering the charges as he leaped into the orange mist of the riptime, and sank the Titanic.

Thinking, crankily, There's gotta be an easier way to make a living. A guy could get hurt like this!

"THAT'S A FEDERAL OFFENSE you're suggesting, Mr. Auld. It's not just my job, it's the whole franchise. The auditors come in, they fall over it — because I don't know how to cover it — and the people who own this Bank lose everything they sank into it." The young woman stared at Jerry Auld till he looked away. She wasn't trying to be kind, despite the look of desperation on his face. She was telling him in as flat and forthright a manner as she could summon — just in case he was a field investigator for the regulatory agency looking for bootleg Banks — possibly wired for gathering evidence — so he would understand that this Memory Bank was run strictly along the lines of the Federal directives.

"Is that what you want, Mr. Auld? To get us in the most serious kind of trouble?"

He was pale and thin, holding his clasped hands in his lap, rubbing one thumb over the other till the skin was raw. His eyes had desperation brimming in them. "No . . . no, of course not. I just thought. . ."

She waited.

"I just thought there might be some way you could make an exception in this case. I really . . . have to get rid of this one last, pretty awful memory. I know you've gone as far as you can by the usual standards; but I felt if you just looked in the regulations, maybe you'd find some legitimate way to . .

"Let me stop you," she said. "I've monitored your myelin sheathing, and the depletion level is absolutely at maximum. There is no way on earth, short

of a Federal guideline being relaxed, that we can leach one more memory out of your brain." She let a mildly officious — some might say nasty — smile cross her lips. "Simply put, Mister Auld: you are overdrawn at the Memory Bank."

He straightened in the formfit and his voice went cold. "Lady, I'm about as miserable as a human being can be. I've got a head full of stuff that makes sex with spiders and other small, furry things seem like a happy alternative, and I don't need you to make me feel like a fool."

He stood up. "I'm sorry I asked you to do something you can't do. I just hope you don't come to where I am some day and need someone to help."

She started to reply, but he was already walking toward the iris. As it dilated, he turned to look at her once more. "You don't look anything like her. I was wrong."

Then he was gone.

It took her some time to unravel the meaning of his last words; but she decided she had no time to feel sorry for him. She wondered who "her" was; then she forgot it.

The little man with the long nose and the cerise caftan spotted Auld as he left the Memory Bank. He had been sitting on a bench in the mall, sipping at a bulb of Flashpoint Soda, watching the Bank. He recognized Auld's distressed look at once, and he punctiliously deposited the bulb in a nearby incinerator box and followed him.

When Jerry Auld wandered into a showroom displaying this year's models of the Ford hoverpak, the little man sauntered around the block once, strolled into the showroom, and sidled up to him. They stood side-by-side, looking at the pak.

"They say it's the same design the aircops use, just less juice," the little man said, not looking at Auld.

Jerry looked down at him, aware of him for the first time. "That so? Interesting."

"You look to me," the little man said, in the same tone of voice he had used to comment on the Ford pak, casual, light, "like a man with some bad memories."

Jerry's eyes narrowed. "Something I can do for you, chum?"

The little man shrugged and acted nonchalant. "For me? Hell, no. I'm fuzz-free and frilly, friend. What I thought, I might be able to do something upright for you."

"Like what?"

"Like get you to a clean, precise Bank that could leach off some bad stains."

Jerry looked around. The showroom grifters were busy with live customers. He turned to face the little man.

"Why me?"

The little man smiled. "Saw you hobble out of the Franchise Bank in the mall. You looked rocky, friend. Mighty rocky. Carrying a freightload of old movies in your skull. Figured they turned you down for one reason or another. Figured you could use a friendly steer."

Jerry had been expecting something like this. The Bank in the mall had not been his first stop. There had been the Memory Bank in the Corporate Tower and the Bank in the Longacre Shopping Center and the Bank at Mount Sinai. They had all turned him down, and from recent articles he'd read on bootleg memory operations, he'd suspected that maintaining a visible image would put the steerers on to him.

"You got a name, chum?"

"Do I gotta have a name?"

"Just in case I go around a dark corner with you and get a sap upside my head. I want to be able to remember a tag to go with the face."

The little man grinned nastily. "Remember the nose. My friends call me Pinocchio."

"Let's go see the man," Jerry Auld said.

"Woman," Pinocchio said.

"Woman," Jerry Auld said. "Let's go see the woman."

The bootleg Bank was on an air-cushion yacht anchored beyond the twelve-mile limit. They reached it using hoverpaks, and by the time the strung lights of the vessel materialized out of the mist, it was night. They put down on the forecastle pad and racked their units. Pinocchio kept up a line of useless chatter, intended to allay Auld's fears. It served to draw him up tighter than he'd been before the little man had braced him.

Jerry saw guards with weapons on the flying bridge.

Pinocchio caught his glance and said, "Precautions."

"Sure."

Pinocchio didn't move. Jerry said, "Are we doing something here or just taking the night air?" He didn't like being under the guns.

Pinocchio kept his eyes on the flying bridge as he said, "They're making us: reporting. It'll only be a minute."

"What kind of trouble do these people get?" Jerry asked.

"Hijackers sometimes. You know: pirates. The market's lively right now. A lot of jockeying for territory, getting good product to push . . . " One of the armed guards motioned with his weapon, and Pinocchio said, "Come on."

They went belowdecks. The yacht was handsomely appointed. Flocked-velvet wallpaper in the companionways, burnished metal banisters, thick carpets. Pinocchio knocked at an inlaid teak door. The door was opened by an unexceptional-looking woman. She smiled, pro forma, and walked back into the cabin, permitting Auld and the little man to enter.

The room was a spacious saloon, fitted to the walls with the memory-leaching devices Auld recognized from his many trips to legitimate Banks in the city.

"Ms. Keogh, I'd like to introduce Mr. Jerry Auld. Met him in the city, thought we could do a little business . . . "

She waved him to silence. "Do you have your own transportation, Mr. Auld? Or did you come with Mr. Timiachi?"

Auld said, "I have my own pak."

"Then you can go, Mr. Timiachi," she said to the little man. "Stop by the office and get a check."

Obsequious, Pinocchio bobbed his head and smiled a goodbye at Jerry. Then, sans forelock-tugging, he bowed himself out of the saloon. Ms. Keogh waved at a formfit. Jerry sat down.

"How close are you to maximum depletion?" she said.

He decided not to fence. He was in too much pain. They were both here for the same thing. "I'm at the limit."

She walked around the saloon, thinking. Then she came and sat down beside him in the other formfit. Through the open porthole Auld heard the mournful sound of something calling to its mate across the night water. "Let me tell you several things," she said.

"I want to get rid of some bad stains," Auld said. "I know what I need to know."

She raised a hand to silence him. "Probably. Nonetheless, this is not a bucket shop. Bootleg, yes; but not a crash and burn operation."

He indicated he'd listen.

"The 'holographic' memory model postulates that a memory is stored in a manner analogous to a hologram — not sited in any specific area, but stored all over the brain. To remove one certain memory, it is always necessary to break molecules of myelin allover the brain . . . from the densely packed myelin of the corpus callosum —"

"The white matter," Auld said. She nodded. "I've heard all this before."

"— from the white matter right down the spinal cord; perhaps even down into the peripheral nerves." She finished on a tone of dogged determination.

"Now tell me about the weak point in the long-chain myelin molecule. The A-1 link. Tell me how easily the molecule breaks there. The point at which muscular dystrophy and other neurodegenerative diseases attack the molecule. Tell me how I might become a head of lettuce if I go past the max. I've heard it all before. I'm surprised you're trying to discourage me. I'm also annoyed, lady."

She looked at him with resignation. "We don't push anyone; and we don't lie. It's bad enough we're outside the law. I don't want anyone's life on my hands. Your choice, fully informed."

He stood up. "Put me in the drain and let's get this over with."

"It must be nasty."

"I pity the poor sonofabitch you sell these stains to."

"Would you like to meet the head that will be receiving what you'll be losing?"

"Not much."

"He's a very old man whose life has been bland beyond the telling. He wants action, danger, adventure, romance. He wants to settle into his twilight years with a head filled with wonder and experience."

"I'm touched." He made his fists. "Goddammit, lady, get this shit out of my head!"

She waved him to the leaching unit on the wal

l. He followed her as she opened out the wings. She folded down the formfit with its probe helmet, and he sat without waiting for instructions. He had been in that seat before. Perhaps too many times.

"This won't hurt," Ms. Keogh said.

"That's not true," he replied.

"You're right. It's not true," she said, and the helmet dropped and the probes fastened to his skull and she turned on the power. The universe became a whirlpool.

Lucy spat blood and he touched her chin with the moist cloth. "Jerry, please."

"No. Forget it."

"I'm in terrible pain, Jerry."

"I'll call the medic."

"You know it won't do any good. You know what you have to do."

He turned away. "I can't, kid. I just can't."

"I trust you, Jerry. If you do it, I won't be afraid. I know it'll be okay."

It wasn't going to be okay, no matter how it happened. For a moment he hated her for wanting to share it with him, for needing that last terrible measure of love no one should be asked to give.

"Don't let them put me in the ground, Jerry. Nobody can talk to worms. Send me to the fire. I wouldn't mind that, not if you were with me . . ."

She was rambling. He understood about her fear of the dark; down there forever in the cold; with things moving toward her. Yes, he could guarantee the clean fire would have what remained . . . after. But she was rambling, talking about things she was seeing on the other side —

"I know they're over there, past the crossover, Jerry. They were there before, when I thought I was going. Don't let me die alone. Be there to keep them at bay till I can run, honey. Please."

She coughed blood again, and her eyes closed. He held the moist cloth and reached down and lifted her head from the pillow and placed it over her face. "I love you, kiddo."

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

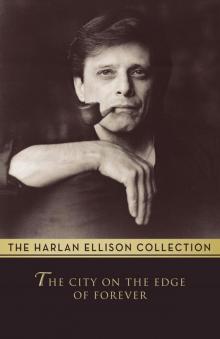

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

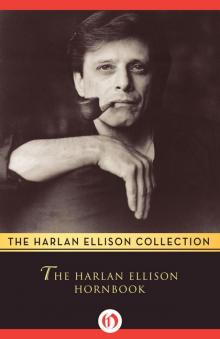

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

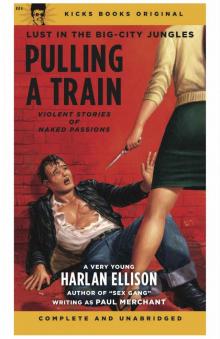

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage