- Home

- Harlan Ellison

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Page 3

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Read online

Page 3

It must have been hell for everyone inside the house, the sound of that ball plonking against the wood, again and again, without end, till it got too dark to see it.

We moved away from there soon after, and I went from straight As in school to failing grades in everything. I became a trouble kid of the worst sort. But it worked out.

Ever since then, I now realize, I’ve been looking for my Father. I’ve tried to find him in Dad-surrogates, but that’s always come to a bad end. And all I ever wanted to tell him was, “Hey, Dad, you’d be proud of me now; I turned out to be a good guy and what I do, I do well and…I love you and…why did you go away and leave me alone?”

When I lived in Cleveland, I used to go to his grave sometimes, but I stopped doing that fifteen years ago and haven’t been back.

He isn’t there.

INSTALLMENT 2 | 2 NOVEMBER 72

VALERIE, PART ONE

Here’s one I think you’ll like.

In this one I come off looking like a schmuck, and don’t we all love stories in which the invincible hero, the all-knowing savant, the omnipotent smartass is condignly flummoxed? It’s about Valerie.

About 1968 I knew this local photographer named Phil. He wasn’t the world’s most terrific human being (in point of fact, he was pretty much what you’d call your garden-variety creep), but he somehow or other wormed his way into my life and my home—I believe wormed is the right word—and occasionally used my residence as the background locale for sets of photos of young ladies in the nude. Phil would show up at my house in the middle of my work-day, all festooned with lights and reflectors and camera boxes…and a pretty girl, whom he would usher into one of the bathrooms and urge to divest herself of her clothing, vite, vite!

Now I realize this may ring tinnily on the ears of those of you who spend the greater part of your off-hours lurching after your gonads, but having edited a men’s magazine in Chicago some years ago, the sight of a lady in dishabille does not cause sweat to break out on my palms. What I’m saying is that after two years of examining transparencies framed in a light-box, while wearing a loupe to up their magnification, all said transparencies of the world’s most physically sensational women, all stark naked…one develops a sense of proportion about such things. One begins looking for more exotic qualities—such as the ability on the part of the ladies to make you laugh or cry or feel as though you’ve learned something. (As an aside: nothing serves better to kill ingrained sexism than an overdose of flesh in living color; very quickly one differentiates between images on film and living, breathing human beings. I commend it to all you gentlemen who still use the words broad and chick.)

Consequently, it was not my habit to skulk around the house while Phil was snapping the ladies. When they’d take a break, I’d often sit with them and have a cup of coffee and we’d enter into a conversation, but apart from that I’d generally sit in my office and bang the typewriter. This may seem to have been the wrong thing to be banging, but, well, there you are. (Because of this attitude, Phil drew the wholly erroneous conclusion that I was gay, and had occasion, subsequently, to pass along his lopsided observation, sometimes to young ladies with whom I had become intimate. What a nasty thing to say, particularly from a man who lures six-year-old boys into the basements of churches and then defiles, kills and eats them, not necessarily in that order. Isn’t idle gossip a wonderful thing!)

This use of my home and myself by The Demon Photographer went on for about a year, and I confess to permitting the inconvenience because on several of these shooting dates I did meet women with whom I struck up relationships. One such was Valerie.

(Of course I know her last name, you fool. I’m not giving it here out of deference to her family and what comes later in this saga.)

The Demon Photographer—squat, ginger-haired, insipid—arrived one afternoon with her, and I was zonked from the moment I saw her. She was absolutely lovely. A street gamine with a smile that could melt jujubes, a warm and outgoing friendliness, a quick wit and lively intelligence, and a body that I would have called dynamite during my chauvinist period. We hit it off immediately, and when Phil slithered away at the end of the session, Valerie stayed on for a while.

It didn’t last all that long, to be frank. I can’t recall all the specifics of disenchantment, but attrition set in—it’s happened to all of you, so you know what I mean—and after a short while we parted: as friends.

Over the next few years, Valerie popped back into my life at something like six-month intervals, and if I wasn’t involved with anyone we’d get it on for a few days, and then away she’d fly once more. There was always a kind of bittersweet tone to our liaisons: the scent of mimosa (and mimesis, had I but known), dreams half glimpsed, the memories of special touches. There was always the feeling that something lay unspoken between us, and a phrase from Sartre’s THE REPRIEVE persisted: “It was as if a great stone had fallen in the road to block my path.” In a way, I believe I was in love with Valerie.

Time passed. In mid-May of 1972 I was scheduled to speak at the Pasadena Writers’ Week, and early the day of the appearance, I received a call from Valerie. I hadn’t heard from her in almost a year.

After the hellos and my unconfined pleasure at hearing her voice, I asked, “What are you doing tonight?”

“Going out with you,” she said.

(Witness, gentle readers: the desiccated ego of The Author, suddenly pumped full of self-esteem and jubilation, merely refractions of adoration at the perceptivity and swellness of a bright, quick lady saying, “You’re fine.” What asses we machismo buffoons can be.)

“Listen, I’m slated to go out and speak in Pasadena to a gaggle of literary types. Why don’t you go with me and watch how I turn the crowd into a lynch mob.”

“That’s where I am,” she said. “In Pasadena. At my mother’s house. You can pick me up and I’ll stay with you for a couple of days.”

“I’ll buy that dream,” I said, and we set up ETA and coordinates.

That evening, in company with Edward Winslow Bryant, Jr. (dear friend, sometime house guest, outstandingly talented young writer, author of AMONG THE DEAD, CINNABAR, and co-author of PHOENIX WITHOUT ASHES) I drove out to Pasadena to pick up Valerie. When she answered the door she paused momentarily, framed in the opening, wearing a dress the shade of a bruised plum; as said, a body that should have been on permanent exhibition in the Smithsonian; wearing nothing under it.

Oh, Cupid, you pustulent twerp! One of these days some nether god is going to jam that entire quiver of crossbow bolts right up your infantile ass!

I went down like a bantamweight in an auto chassis crusher.

Carrying her overnight case, her hair dryer and curlers, her suitcase, her incredibly sweet-smelling clothes on wire hangers, I took her to the car, and was rewarded by the sight of Ed Bryant’s eyes as they turned into Frisbees. Not to mention the unsettling memories of the hugs and kisses and liftings off the floor and spinnings around I’d just received inside the house.

We did the speaking gig, and Valerie sat in the front row displaying a thoroughly unnerving expanse of leg and thigh. I may have fumfuh’d a bit.

Afterward, Valerie, Ed and I went to have a late dinner at the Pacific Dining Car. Sitting over beefsteak tomatoes and the thickest imported Roquefort dressing in the Known World, Valerie started whipping numbers on me like this:

“I’ve always had a special affection for you. I should have moved in with you three years ago. Boy, was I a fool.”

I mumbled things of little sense or import.

“Maybe I’ll move in with you now…if you want me.”

The next day, a girl from Illinois was to have flown in for an extended weekend. “Give me a minute to make a phone call,” I said, and sprinted. I made the call. Bad vibes. Harsh language. Dead line.

“Yeah, why don’t you move in with me,” I said, slipping back into the booth. Everyone smiled.

When she went to the loo, Ed—whose perceptions about peopl

e are keen and reserved—leaned over and said, “Hang onto this one. She’s sensational.”

Opinion confirmed. By a sober outside observer.

So I took her home with me. The next day, Ed split for his parents’ home in Wheatland, Wyoming, beaming at Harlan for his good luck and prize catch. That left, in the household, myself, Valerie, and Jim Sutherland: young author of STORMTRACK, occasional house guest and ex-student of your humble columnist at the Clarion Writers’ Workshop in SF & Fantasy.

Later that day, Valerie asked me if she could use the telephone to make a long distance call to San Francisco. I said of course. She had told me, by way of bringing me up to date on her peregrinations, that since last she’d seen me she had been working in San Francisco, mostly as a topless waitress at the Condor and other joints; that she had been rooming with another girl; that she had been seeing a guy pretty steadily, but he was into a heavy dope scene and she wanted to get away from it; and she loved me.

After the call, she came into my office in the house and said she was worried. The guy, whom she’d called to tell she was not coming back, had gotten rank with her. The words bitch and cunt figured prominently in his diatribe.

She said she wanted to fly up to San Francisco that day, to clean out her goods before he could get over there and rip them off or bust them up. She also said, very nicely, that if she went up, she wanted to buy a VW minibus from a guy she knew. It would only cost $100 plus taking over the payments, and she’d need a car if she was going to come back here to live. “I want to work and pay my way,” she said.

Or in the words of Bogart as Sam Spade, “You’re good, shweetheart, really good.” Remember, friends, no matter how fast a gun you are, there’s always someone out there who’s faster. And how better to defuse the suspicions of a cynical writer than to establish individuality and a plug-in to the Protestant Work Ethic.

She asked me for the hundred bucks.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have the hundred at that moment, even though I said credit-card-wise I’d pay for her plane ticket to San Francisco.

She said that was okay, she’d work it out somehow. Then she went to pack an overnight bag, leaving all the rest of her goods behind, and promised she’d be driving back down the very next day.

Jim Sutherland offered to drive her to the airport—I was on a script deadline and had to stay at the typewriter—and she left with many kisses for me and deep looks into my naive eyes, telling me she was all warm and squishy inside at having finally found me, Her White Knight.

It wasn’t till Jim returned, young, innocent, a college student with very little bread, that I found out she had asked him for the hundred bucks, too. And he’d loaned it to her, with the promise of getting it back the next day.

The worm began to gnaw at my trust, but I decided to wait and see what happened.

…as you will have to wait, till next week, when I conclude this two-part revelation of gross stupidity and chicanery, under the general title: VALERIE, COME HOME!

INSTALLMENT 3 | 9 NOVEMBER 72

VALERIE, PART TWO

Valerie, the Golden Girl, the Little Wonder of the Earth, having fundanced her way into my life again, had now cut out for San Francisco with a hundred dollars of Jim’s money. But she’d said she could manage somehow without the hundred…

If she’d needed it that badly, after I’d said I didn’t have it, why didn’t she ask me again, rather than come on with a kid she’d just met a day earlier? How the hell had Jim come up with that much bread on the spur of the moment?

“We stopped off at my bank on the way to the airport,” he said. I was very upset at that information.

“Listen, man,” I said, “I’ve known her a few years and she’s not even in the running as the most responsible female I’ve ever known. I mean, she’s a sensational lady and all, but I don’t really know where she’s been the last few years.”

Jim suddenly seemed disturbed. That hundred was about all he had to his name. He’d earned it assisting me in the teaching of a six-week writing workshop sponsored by Immaculate Heart College, along with Ed Bryant; and he’d worked his ass off for it. “She said she’d borrow it from a friend in San Francisco and get it back to me tomorrow.”

“You shouldn’t have done it. You should’ve called me first.”

“Well, I figured she was your girl, and she was going to live here. And she said there wasn’t time to call if she was going to make the plane, so…”

“You shouldn’t have done it.”

I felt responsible. He’d been trusting, and kind, and I had a flash of uneasiness. The old fable about the Country Mouse and the City Rat scuttled through my mind. Valerie had been known to vanish suddenly. But…not this time…not after her warmth and protestations of love for me…that was unthinkable. It would work out. But if it didn’t…

“Listen, anything happens, I’ll make good on the hundred,” I told him.

And we settled down to wait for Val’s return the next day.

Two days later, we reached a degree of concern that prompted me to call her mother. The story I got from her mother did not quite synch with what Valerie had told me. Valerie had said she’d told her mother she was moving in with me; the mother knew of no such thing. Valerie had told her she was working in Los Angeles; Valerie had told me she would try and get a job when she returned from San Francisco. The worm of worry burrowed deeper.

Using the phone number of Valerie’s alleged apartment in San Francisco, I got a disconnect. No word. No Valerie, no word of any kind. Had her ex-boy friend murdered her? Had she bought the VW bus and run off the road?

Students of the habit patterns of the lower forms of animal life will note that even the planarian flatworms learn lessons from unpleasant experiences. I was no stranger to ugly relationships with (a few, I assure you, a very few) amoral ladies. But homo sapiens, less intelligent than the lowest flatworm, the merest paramecium, repeats its mistakes, again and again. Which explains Nixon. And also explains why I was so slow to realize what was happening with Valerie. It took a sub-thread of plot finally to shine the light through my porous skull. Like this:

In company with Ray Bradbury, I was scheduled to make an appearance at the Artasia Arts Festival in Ventura, on May 13th. That was the Saturday following Valerie’s leavetaking. Ray and I were riding up to Ventura together, and though I’m the kind of realist who considers cars transportation, hardly items of sensuality or beauty, and for that reason never wash my 1967 Camaro with the 74,000 miles on it, I felt a magic man of Bradbury’s stature should not be expected to arrive in a shitwagon. So I asked Jim to take my wallet with the credit cards, and the car, and go down to get the latter doused. I was still chained to the typewriter on a deadline, or I would have done it myself.

Jim took it to a car wash, brought it back, and returned my wallet to the niche in my office where it’s kept at all times. Aside from this one trip out of the house, the wallet (with all cards present) had not been out of my possession for a week.

The next day, Saturday, Ray came over and I drove us up to Ventura. After checking in, we went to get something to eat. At the table, I opened my wallet to get something—the first time I’d opened the wallet in a week—and suddenly realized some of the glassine windows that held my credit cards were empty. After the initial panic, I grew calm and checked around the table, covered the route back to the car, inspected the map-cubby where I always keep the wallet, looked under the seats…and instantly called Jim in Los Angeles to tell him I’d been ripped off.

Since the wallet had only been out of the house once in the last week, the cards had to have been boosted at the car wash. Do you see how long it takes the planarian Ellison to smell the stench of its own burning flesh?

I called Credit Card Sentinel, the outfit that cancels missing or stolen cards, advised them of the numbers of the cards (I always keep a record of this kind of minutiae handy), and asked them to send the telegrams that would get me off the hook immediately. There’s a law

that says you can’t get stuck for over fifty bucks on any one card, but there were five cards missing—Carte Blanche, BankAmericard, American Express, Standard Chevron Oil and Hertz Rent-A-Car—and that totaled two hundred and fifty dollars right there; with Sentinel, the effective lead-time for use of the cards is greatly reduced.

Having deduced á la Nero Wolfe that the thief had to have been the dude who swabbed out the interior of the car at the washatorium, I called the West L.A. police, detective division, the area where the car wash was located, and put them on to it. I called the owners of the car wash and relayed the story, and tried to coordinate them with the detective who was going to investigate, advising them that they should check out the guys who’d worked interiors that previous Friday, noting especially any who hadn’t shown up for work.

My detective work was flawless…aside from the sheer stupidity of my emotional blindness.

You all know what happened.

But I didn’t, until five days later, when I received a call from the BankAmericard Center in Pasadena asking me to verify a very large purchase of flowers sent to Mrs. Ellison in the Sacramento, California Medical Center. I assured them there was no Mrs. Ellison, I was single, and the only Mrs. Ellison was my aged mother, in Miami Beach.

The charge, of course, was on my stolen card.

Then the light blinded me.

The next day, I received a bill for forty-three dollars from the Superior Ambulance Service in Sacramento, a bill for having carted someone from a Holiday Inn to the Sacramento Medical Center on May 13th. The name of the patient was Ellison Harlan and the charge had been made to my home address.

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

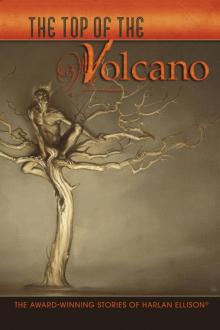

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage