- Home

- Harlan Ellison

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation Page 15

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation Read online

Page 15

I mean, I knew what that sonofabitch thought of me: he thought I was fay, that I didn’t dig Negroes. How wronger could he get? It wasn’t his color I hated, it was that slob Kurt himself, I mean, him personally.

“C’mon, man, let’s go here, I got some burgers to fry.”

Why that lyin’ sack of—

He was the Shack’s cook, all right, but it was just as easy to take strychnine as eat his greaseburgers. And he knew I knew damned well when he disappeared for some craps or cards Dotty would take over at the grill. He knew I knew.

He just wanted to keep me locked up in there, with his big foot plastered against the locked door, and his fist all ready-made to belt me up alongside the head if I made any noise to anyone on the other side of that toilet door. I was as salted away in there with him as I’d ever been in the junk farm at Lex, or the Tombs or any other damn slammer. I was fried. He knew it. He knew I was sick and getting worse, and he wasn’t about to pay off.

To top it off, Kurt had that gravity knife of his.

That big aluminum-handled shake knife that he could whip out so fast it looked like he didn’t have a hand, but some kind of a metal hook at the end of his arm. I was scared of him, all right.

Why, I remember one night when some joker busted on Kurt behind the grill, telling him the eggs were greasy, and dumping the plate down on the breadboard. Kurt didn’t even say anything, he just grabbed that muthuh by the neck and dragged him over the counter and beat the crap outta him, and then picked him up by the neck and the seat of his pants and heaved him—I mean he heaved that two hundred pounder—right out of the kitchen and into the second booth down the line.

Kurt was big and muscular and nasty, real nasty, so I wasn’t about to fool with him. He’d said the door was locked till we were done, that was it!

“One of us gonna leave here broke, man,” he’d said when we had entered the toilet. “One of us gonna be Tap City.”

My first mistake had been in getting caught short when I needed a fix. That was the first thing. My second mistake was busting on Kurt for the ten bucks he’d owed me for six or seven months. I needed the money, I had twenty-five and that last ten would have made the tariff for my Man waiting out there, but Kurt had gotten a sly look in his eyes—Jeezus, he was a rotten cat—and said, “Tell you what, Teddy, tell you what, man. I’m gonna shoot a little high dice with you, make that bread sing. Howzabout?”

I knew he cheated. Everybody did. He used bombed ivories, loaded down with every kind of BB shot and scrap metal left over from World War II, but I had no choice. I mean, I figured if I had him and had him cold so he couldn’t lie or cheat or con his way out of it, he’d come up with the ten. Guys like that feel easier about losing loot in a game than paying back an honest loan. Man, was I snowing myself!

So I’d said yes and gone into the toilet at the Shack with the cook, Kurt, and the pains came and the hurt came and I was golden so help me very golden, and I couldn’t lose, and Kurt was getting nearer and nearer killing me with his cold, flat eyes and his big aluminum-handled shake knife.

But what could I do?

“Say, look, Kurt.” I came on very logical, very pleasant, trying to convince him and me that I wasn’t in pain and had to get it soon or die. “Now, dig. I’ve won a hundred and forty bucks from you, this isn’t your night, man. Now look, all I want is that ten…that’s all. Just give me the ten and we’ll call it square. Good?”

“Stop jivin’ me and fire them dice.”

He looked up from where he was hunkered on the dirty floor, and I hope I never see a look like that again. It was killing cold.

And then I dug. Then I realized what I should have known right in front: that bastard didn’t have any money at all. He didn’t have a hundred and forty or ten or any other damn thing. He was busted. And he’d been bluffing me, playing me on my own money!

I wanted out then, very bad.

“Okay.” I said, “forget it you—” I started to call him a bastard, but stopped, bad move, “—you don’t have to pay me now. Just forget it. Just lemme out of here.” He didn’t budge. He wanted what I had on me. I don’t know why, and I don’t care, but he was insulted, somehow. He owed me money and he hadn’t been able to take me, and he was killing mad because the ofay bastard had him a hundred and forty mythical dollars in the hole. It was suddenly more than a crap game, it was a status thing, the downtown black man and all that. He was a sick guy, putting all that into it, and me just wanting to get the hell out of there and forget the ten, I’ll get it off a friend or some damn thing. Just lemme outta here!

“I’m gone pay you, man, you just remember that. But we gonna play a bit more. We gonna switch from crap, you been winning too much.” He reached into his side pocket and took out that knife, the one I knew he had.

He didn’t do a thing with it, just laid it back down in his sock, right tight to the shoetop. He was giving me the word, I’d better not win.

Better not win? Jeezus, what’d I have to do, kill myself to prove I didn’t want to win?

“High dice, now,” he said succinctly.

He picked up one of the dice and bounced it, so very white, in the center of his palm, so very black. He was really busting on the symbolism. “You throw for roller,” he bid me, and my head swam for an instant, everything going furry and grey and I wanted to puke right there.

I threw the cube and it came up six.

Then he threw, and got a three, and I was roller, first.

High dice is played sometimes with two, sometimes with one, but the rule is simple: high man wins. I was his master for a hundred and forty, and this was a quick, frantic way to recoup fast. It’s a sucker’s game.

“Look, Kurt,” I almost pleaded with him, “please, I’m not feeling too well, let me get out of here, will you? You can forget the money, just let me out of here.” It was the wrong thing to do; he wanted me to crawl, it was some kind of a thing with him to see me completely hammered and half dead on my feet and the Man still waiting outside there, and me not being able to move, hanging suspended like a fly in a web.

“I think you been cheatin’ me, Teddy,” he said, rising, towering over me as I crouched down. “I think you been doin’ tricks with them dice. Gimme ’em here.” He reached down and I gave him my cube. He put them in his side pocket and took a smaller, red plastic pair out of his shirt pocket. They were clear plastic and I could see right through them and I knew as sure as hell they were loaded, the spots painted on with lead paint.

“Well, listen, Kurt,” I said righteously, “that other set was yours, too, so where the hell you get this stuff I’m cheating. Now c’mon, for Chrissakes, just get away from that door and let me out of here!”

I was getting a little hysterical now, and even as I raised my voice to him, someone shook the knob and banged half a dozen times quickly with a fist on the door and I heard a voice from the other side of the wood panel yell, “Hey, c’mon you jerks what the hell’s going on in there, you a pair of fruits, or what?” and banged again. I was really going out of my mind about then. I started to yell help to whoever was there but Kurt just reached out lightly and slapped me so hard across the mouth I thought my skull would split open. I didn’t get rocked back or anything, but it was the hardest I’ve ever been hit—and it dawned on me that I hadn’t had a fight since I was thirteen years old, and how easy it was to avoid violence if you were always afraid, and just never had occasion to fight because you didn’t want any part of it. But this was real, not the kind of constant wearying violence they have on TV that has no reality because there’s such a surfeit of it.

I got hit in the mouth, and I wanted to cry at him.

Then I did cry, I really cried, with tears, and my hands were wringing each other and I was begging him, “C’mon, Kurt, please c’mon, let me out of here!” I couldn’t give him my twenty-five dollars, I needed it, I needed that fix, my God, help me please help me God I’m going out of my mind, everything’s closing in on me, I’ll strangle

if I don’t get a fix, JeezusJeezusJeezus!

“Man, you really think you gonna do that to me, doncha? You really think ah’m gonna let you outta here with mah money! Now c’mon, damn you, you gone play a little high dice with me, and then…when you get straight…I’ll let you go.”

It wasn’t real, what was happening. A nightmare, this weird surrealism bit with him saying one thing and meaning another. I didn’t have any of his money…in fact, he had ten bucks of mine! It wasn’t the money, it was the whole thing of him being him and me being me and he had to beat me down. I mean, Jeezus, here I was on my knees already crying like a baby, and begging him, what the hell else did he want from me.

I felt everything going strange and wild and brass bands were marching through and outside in the Shack everyone could see through the walls and see how I was getting so sick I wanted to die, and I was seeing things, crawly things that were coming up to bite the hell outta me. I knew the Man was sitting there maybe wiping his hands on his pant leg, or picking his nose, making those tentative first movements that meant he was gonna pick up and split at once, and there would go my fix and I’d just croak, and that would be it. It!

That little toilet was the world, right then.

It was the biggest and blackest most angry Negro in the world, all ready to kill me for every white cat that had ever used the word nigger. And I was innocent, so help me God.

The room bulged outward, rubber walls ballooning.

The floor puckered.

I hurt worse and worse. My belly was blasted.

My head throbbed and beat and beat and beat.

Well: it passed, and I was sane again for a second. It had been very bad, all those twisting illusions and strange, dancing colors. I had been out of it completely, but now I was all right (except for the pains) and I had to take very close stock. Now just breathe easily, deeply, and look around. Just forget Kurt there for the moment. What else is there. Well…

The toilet has green walls, linoleum halfway up of a deeper green, and a sort of colorless dirty linoleum floor, and a toilet with the seat up and someone’s stuff still there, along with the floating seaweed of a cigarette, and a permanent ochre stain around the bowl. There’s a cloth towel rack up there over the sink, with the towel at the end of its tracks and hanging down into the sink. It’s very dirty, and some people will wipe their hands anywhere. There’s a mirror on the front of that towel rack, but it’s too high for me to see myself in it. I’m not too tall and Kurt is so goddam big—uh-uh, not Kurt. Analyze the room; what else…

Well, there’s the sink, without any handles on the faucets, because the jerks who come here would leave the water running if there were. The hot water one is letting down a soft dripping thin stream, just enough to moisten your hands or get some wet on the comb, but since there’s no soap, who cares? There’s a can of Bab-O on the sink.

They don’t have the Gold Dust twins on it any more. Or was it a Dutch girl with a bonnet that hid her face? I don’t know.

There’s a grille up in the wall that’s between the men’s and women’s johns, but you can’t hear much for some reason or other (I know some guys had wanted to hear what their dates were saying after a prom one night, and they could only make out mewling sounds). There is a line wrench with an octagonal socket on the end, leaning against the wall under the sink, so the mains can be turned off completely. Why bother? There isn’t enough water coming out to count.

The room is about three-and-a-half feet across.

It is something over nine feet long.

It is very high, maybe ten or eleven feet high.

And all at once, I know it is shaped just exactly like a coffin, a coffin goddamit! A coffin and I’m buried with this no-good sonofabitch Kurt, who wants me dead and now I’m dead with him in the motherin’ coffin with me, and that makes no sense at all, and I get very angry about it when I think about it…

“C’mon, throw, double mah bet,” Kurt said, and I came up from way down there, angrier than anything, and just stood there watching those two red plastic dice in his hand that I knew, I mean, I knew they were ringers, so what the hell did he think I was, a nut or something!

“I don’t want to play with those dice,” I said.

So I’d opened my big mouth and put down his whole race—that sick bit again—by calling him a cheater. “Teddy, what you doin’?” he asked, and he was so soft it was painful, because I knew he wanted to swing on me, it was that coughing, whispery voice. “What you doin’, man? You sayin’ I’m not straight…that what you sayin’ to me?”

Oh jump, oh jump jump jump, he’s gonna bust on me any second now, I knew it! “No, listen, hey, I just don’t want to shoot any more. I mean, c’mon, you can’t keep me in here against my will (he laughed at that, short and sharp). You know damned well Bernie’ll wonder where you are.”

Bernie ran the Shack, but I guess he was afraid of that mean streak in Kurt, too, because he warned and threatened him with firing and stuff, but he never did anything, and Kurt was about as afraid of him as he was of me, which was not at all.

“Now, c’mon!” I shouted. “I’m a free guy and you can’t keep me in here, what are you, nuts or something?” Pow! The pain was back, back again from wherever it had been and I learned it hadn’t been bad at all before. Now it was bad.

I flopped toward him, tried to hug him, show him my love. “Please, please, please, Kurt, please lemme outta here, I’m sick, I’m very sick, I’m dying, Kurt. Please, he’ll leave!”

He shoved me back, and said: “Stop tryin’ to whup the game on me, boy. Just shoot.”

He pushed me down by the back of my neck and I had one bloody die in my hand, and the shaking was so bad it looked like every last die in the world was right there, in the oily palm of my hand.

I threw it against the wall:

How did you get hooked? How the hell did you stop being a simple-minded college sophomore who went to the Heidelburg for beer and jazzed around at the fraternity house, and dated balling chicks with nice smooth shins above their bobby socks, and became a junior who needed more money for junk than he did for books or tuition? How did you get so screwed up that you wind up on your knees in a toilet, golden, crying like a psycho? Boy, is this ever miserable…

It clattered to a stop and lay there very square, very red, and very six.

Kurt called me a dirty name.

He threw his, and it was a five. Ding! Just like that. Two hundred and eighty dollars. Two hundred and eighty punches in the mouth he was going to give me. I had won with his own loaded square cube dice, oh boy that was it!

“Sheet, sheet, sheet!” he cursed, drumming at that brown colorless linoleum. Oh, God, was he mad. Mad isn’t enough of a word for it. He was so mad he wanted to tear my eyes out. Then he picked up those dice and threw them into the toilet!

I had to vomit.

“Hey, get away from the sink!” I shrilled leaping up about as fast as I could. I tried to elbow past him but he grabbed me and spun me back, and the puke which had started up caught midway in my throat—God!—and a little spinnet of dribble hit him on the hand and another on the neck, and that was the end of it. I had spit on him.

You figure it.

The battle of the races was at me all at once.

Why me? I’m innocent I tell you, and he was hitting me, and screaming so loud I knew everyone in the Shack was sitting silent and catching it all, “Who’d you think you are, man, who the eff you think you are you gone spit on me, you—” and he started cursing and hitting me, and so help me God I could barely feel it I was so sick and headachey and vile and wanting to curl up and twitch. He was shrieking and balling and banging on me and I was clattering against those walls like a pea in a pod.

Until he grabbed up that shake knife from his sock and rattled it up into sight, and quiet, so quiet, so very quiet he hissed at me, “You ever been marked, man? You ever been marked?”

And he came on to me. I screamed. I screamed very loud, “Kurt, don

’t cut me, don’t hurt me, don’t cut me, Kurt,” but he was coming, and I just fainted away and was wide-awake as he stumbled over where I’d been, and I was too scared to do anything at all, so I reached under and grabbed his leg. He came back around so gracefully it was pretty to see, and he did a little movement with his knife hand, and I felt a razor go so smoothly through my face, and then there was blood. I mean, just like that, I was cut, and not lightly either. I was cut real good.

He wanted more. He wanted all of me, every bit of my white skin covered red, and he came again, and I scuttled back on my can, across the floor, and my hand hit that line wrench about two feet long, and I swung it up and hit him someplace private with one movement and then hooray, he screamed.

So I got up and belted him again, the sonofabitch.

And then a couple more times.

And I knew my Man was getting quietly up from his table, leaving fifteen cents for a tip, and walking to the front to leave another quarter with his bill, and walking unconcerned out the front door, because he couldn’t afford to be around noise and trouble.

So I hit Kurt another one, just because I wasn’t going to get my fix and was just going to have to puke and die and that was the last of it. I mean, it was so terrible.

When they finally busted down the door I was just sitting there on the floor with my feet against that other wall, about three feet away, and the line wrench hanging down between my knees, and crying, just crying, like a simp.

But what else could I do? I mean, when you hurt as bad as I did, and there was Kurt all dead and messy and me so ill I couldn’t stand it, sitting in my own stuff, it was just hopeless. Just the end of it.

So I wondered all the usual stuff: like why was it I couldn’t lose when I wanted to, and couldn’t win when I wanted to, and why did they keep saying I was going to jail and maybe a nut house, because I knew all that, I knew it, man.

I didn’t get my fix.

I even lost when I wanted to win.

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Broken Glass

Broken Glass Other Glass Teat

Other Glass Teat Memos From Purgatory

Memos From Purgatory I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream The Deadly Streets

The Deadly Streets The Glass Teat

The Glass Teat Paingod and Other Delusions

Paingod and Other Delusions No Doors No Windows

No Doors No Windows Strange Wine

Strange Wine Harlan Ellison's Watching

Harlan Ellison's Watching Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice

Over the Edge/An Edge in My Voice Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison

Troublemakers: Stories by Harlan Ellison Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation

Gentleman Junkie and Other Stories of the Hung-Up Generation The Kyben Stories

The Kyben Stories From the Land of Fear

From the Land of Fear The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison

The Top of the Volcano: The Award-Winning Stories of Harlan Ellison Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed

Sleepless Nights in the Procrustean Bed Ellison Wonderland

Ellison Wonderland Children of the Streets

Children of the Streets Can & Can'tankerous

Can & Can'tankerous Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled

Love Ain't Nothing but Sex Misspelled Stalking the Nightmare

Stalking the Nightmare Approaching Oblivion

Approaching Oblivion Deathbird Stories

Deathbird Stories Partners in Wonder

Partners in Wonder Web of the City

Web of the City Spider Kiss

Spider Kiss A Boy and His Dog

A Boy and His Dog Shatterday

Shatterday Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories

Slippage: Previously Uncollected, Precariously Poised Stories Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman

Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman Come to Me Not in Winter's White

Come to Me Not in Winter's White The Song the Zombie Sang

The Song the Zombie Sang The Other Glass Teat

The Other Glass Teat Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth

Doomsman - the Theif of Thoth The City on the Edge of Forever

The City on the Edge of Forever I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg The Harlan Ellison Hornbook

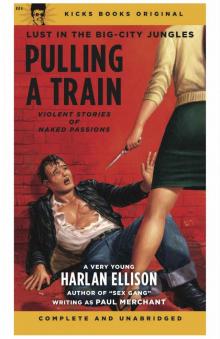

The Harlan Ellison Hornbook Pulling A Train

Pulling A Train The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television

The Glass Teat - essays of opinion on the subject of television An Edge in My Voice

An Edge in My Voice Angry Candy

Angry Candy Troublemakers

Troublemakers The Top of the Volcano

The Top of the Volcano Over the Edge

Over the Edge Survivor #1

Survivor #1 Slippage

Slippage